People of Glen Ellyn

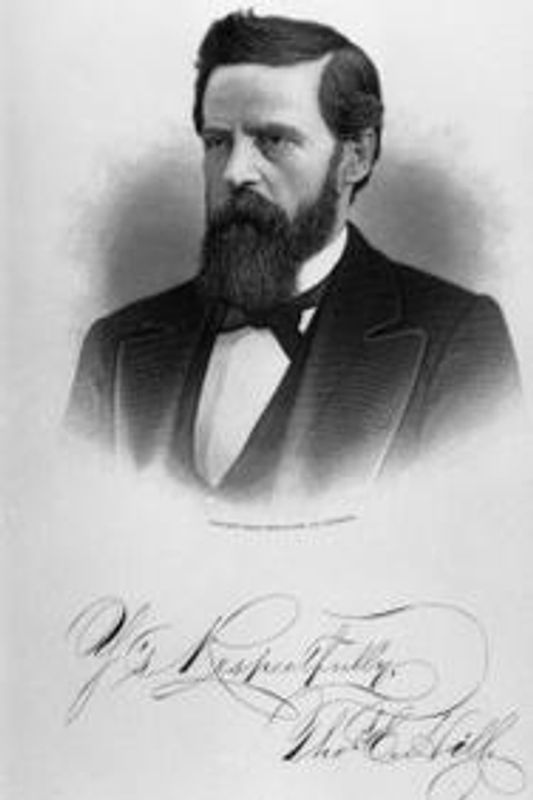

Thomas Hill

Before arriving here in 1885, Professor Thomas E. Hill had been a teacher, a newspaper publisher and a public servant, having served two terms as mayor of Aurora. He also was the author of Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms, regarded by many as the pre-eminent etiquette book of the age. He and his wife, Ellen, brought a new level of sophistication to our town. Both their dress and their manner were refined and they inspired others to follow their lead. Shortly after his arrival, Hill succeeded Joseph R. McChesney as Village President, serving from 1885 to 1889.

Hill also was a visionary and saw how the village, with its attractive rolling terrain and situated as it was on a train line just 25 miles west of Chicago, could become a magnet for folks who wanted to escape the clamor of the big city. To complete the attraction, Hill and several local partners purchased much of the acreage northeast of the downtown area. They dammed a creek to create a beautiful 50 acre lake which Hill called Lake Glen Ellyn (“Ellyn” being the Welsh spelling of his wife’s name), built a 100-room hotel on the hill overlooking the lake, and constructed a nearby pavilion where five different natural springs purportedly offered healing powers. The development of this subdivision coincided with, and arguably encouraged, the building of many of the grand Victorian style homes that also helped the Village overcome its shoddy image.

Recognizing the contribution that Thomas E. Hill and his wife had made, and possibly to capitalize on the appeal Lake Glen Ellyn brought to the community, the town fathers decided in 1891 to change the name of the village to Glen Ellyn.

Without a doubt, there are multiple candidates for the accolade of best leader in the history of Glen Ellyn. But Thomas E. Hill would have to be toward the top of most people’s list.

Lawrence C. Cooper

Mention the “S curve” to anyone who has lived in Glen Ellyn and they know immediately that you’re referring to that section of Park Boulevard just north of the railroad tracks. Few know, however, that this peculiar twist in the road was very deliberate and it was one of many contributions to the Village made by Lawrence C. Cooper.

The Cooper family moved to this area from Clinton County, New York, in 1852 when Lawrence was five years old. They traveled the Great Lakes by steamer to Chicago, and from there by train to the town then called Danby.

Cooper attended school in Danby before getting a law degree from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Before moving back to Danby, he practiced law in Chicago and lived briefly in a room on Chicago’s north side. Shortly before his marriage to Emma Yalding (daughter of Jonathon Yalding, deacon of the First Congregational Church) all of his possessions, including his wedding clothes, were destroyed in the great Chicago fire of 1871. The wedding took place anyway.

Soon after his marriage, Cooper moved back to Danby, joined the legal staff of the Chicago and North Western Railroad, and became one of the early commuters to Chicago using the train. Although he held this post in Chicago for some 50 years, his real contributions were to the community where he lived. These included working with Thomas E. Hill in 1889 to form the company that created Lake Ellyn. Starting in 1902 he served as village attorney for several years, and at various times served on both the village and county boards.

But before any of those involvements Mr. L.C. Cooper introduced the game of baseball to Glen Ellyn, having learned the game while at the University of Michigan. He and a friend organized a team called the Rustics. Shortly after that, Cooper succeeded in luring the Exclesiors of Chicago (the club which later became the Chicago Cubs) to come here and play a game. It did not go well for the Rustics. They lost by a score of 102 to 2.

In 1893, Cooper and his wife built an expansive home on east side of Park Boulevard just north of Anthony Street. In those days, the south end of Park Boulevard stopped at Anthony because of a creek that ran through town just south of that point. In 1914 the village trustees passed an ordinance to channel the creek into a storm sewer and to extend Park Boulevard another block south to Pennsylvania Avenue. At his own expense, Lawrence Cooper paid to incorporate the “S curve” into that road project because he thought that a curve was more interesting and graceful than the straight lines of most streets.

Shortly before he died in 1923, at the age of 76, Cooper published his memoirs, Reminiscences of Old Glen Ellyn, a valuable addition to the history of Glen Ellyn.

Erastus Ketchum

Carpenter, trapper, gun lover and choir boy … all of these labels applied to “Old Ketch,” one of Glen Ellyn’s original citizens.

Glen Ellyn’s early years were populated with a number of people who could be called “characters.” Near the top of this list would be Erastus Ketchum, Jr. who, in 1834 at the age of eight, was a member of the first family to settle what would later become Glen Ellyn. His mother was Christiana Churchill Ketchum, one of the four daughters of Winslow and Mercy Dodge Churchill. Erastus was one of the 13 grandchildren who made the arduous trek from upstate New York to homestead here.

In 1849, when Erastus Ketchum was 23, he married has cousin Mary Jane Churchill, a not uncommon practice in the days when the population around Stacy’s Corners was still pretty sparse and choices for spouses could be slim. They lived for more than 50 years in a house that Erastus built at the southeast corner of St. Charles Road and Main Street.

It was held together with hand-made nails and reportedly had beautiful hand-crafted doors. (The house stood at this location until 1970 when it was demolished to make room for a gas station.)

Ketchum was a farmer and an excellent carpenter, but his greatest exploits were in hunting and trapping wild animals for food and fur. His skills were legendary even among the remaining groups of Native Americans with whom he became friends.

His home was his armory where he kept an extensive array of guns and traps. Historian Ada Douglas Harmon described it as a “veritable arsenal.” He also maintained a cider mill in one of his outbuildings, and farmers would bring wagonloads of apples every fall which he would crush into cider for them, hard cider being a favorite beverage in that era.

Erastus Ketchum was married to the same woman for 50 years and was one of the founders of the Free Methodist Church in town, a church that actively supported the abolitionist (anti-slavery) movement in the pre– Civil War days. He also sang in the church choir and is said to have had a beautiful tenor voice that soared above the rest of the congregation. Erastus Ketchum died in his home at Stacy’s Corners in 1905 at the age of 79.

Madame Emily Rieck

In the early 1900s, Glen Ellyn was enjoying the prosperity that comes from having been discovered as a pleasant resort community by Chicagoans weary of the bustle of the big city. It also was about that time when a reform-minded Chicago major, Carter Harrison, ordered the closing of Chicago’s numerous houses of ill repute. Among them was the luxurious Arena Hotel on Michigan Avenue owned by Emily Rieck (pronounced “Reeck”).

But Madame Rieck was a step ahead of Mayor Harrison. She had visited Glen Ellyn with its scenic lake and convenient rail service. She had found a home, Dr. Samuel Lundgren’s dark Victorian mansion at the corner of Crescent Boulevard and Riford Road. She purchased it, remodeled it extensively and added beautiful landscaping. The house already had a ballroom for dancing. With a few tweaks, this ballroom doubled as a gambling parlor, another revenue source for the enterprising Madame.

Faced with a growing clientele, she soon expanded her operation by building a large guest house at Plum Tree Road, just east of the Lundgren home. Both of these dwellings were a short walk from the Taylor Avenue train stop, a great convenience for gentlemen visiting from Chicago.

According to Russ Ward, author of Images of America — Glen Ellyn, “Platinum blonde Emily Rieck drew the stares of local boys, the ire of reformers, and the quiet gratitude of more than a few residents.” Apparently, at least some of the local wives — many with more children than they could handle — viewed Madame Rieck’s guest house as providing a sort of birth control.

Ada Douglas Harmon

Ada Harmon was born in Champaign, Illinois on August 16, 1860 and moved to Glen Ellyn with two of her sisters in 1892. Much has been written about Miss Harmon. We know, for example, that she graduated from the University of Illinois and the Art Institute of Chicago. She was a painter, a student of Native American culture and the flora of this area, a philanthropist, and author of Glen Ellyn’s first definitive history: The Story of an Old Town–Glen Ellyn.

She was one of the driving forces in the organization of the first public library in the village and a charter member of the Anan Harmon Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

She used her skills as an artist to create a pictorial catalogue of local flora in the form of 175 watercolor paintings later donated to the Morton Arboretum. She died in her home at 577 N. Park Boulevard in 1943 at the age of 82.

Miss Harmon’s Glen Ellyn home still stands at the northeast corner of Park and Glen Ellyn Place. It has received historic status from the Glen Ellyn Historical Society and the Village of Glen Ellyn. In 1892, this area was a new subdivision just one block from the recently created Lake Ellyn.

Alonzo Ackerman

Alonzo Ackerman earned a place in the cast of colorful characters from Glen Ellyn’s early days thanks in part to the way he wore his hair. But as with several other characters from our past, Ackerman did much more than just letting his hair grow.

He was born in 1838 to pioneer settlers John and Lurania Ackerman. Just four years after they settled here, “Lon” Ackerman followed in his father’s foot steps as a hunter, trapper and farmer. In 1856 he married Mary Coffin and they went on to have seven children. In 1858 he heard Abraham Lincoln make a speech at the Danby House in downtown Danby, and when the Civil War broke out he enlisted in the Union Army. His tour of duty included participating in General Sherman’s march to the sea.

When he enlisted, Ackerman was a clean-cut lad. Either during or soon after the war he let his beard grow out and pretty much stopped cutting his hair. From then on he wore his hair in shoulder-length curls. According to Glen Ellyn historian Ada Douglas Harmon, he hosted an event every year on his birthday when he would get his annual haircut.

Adding to his reputation as a character was his habit of driving downtown wearing a cream-colored hat and a navy blue coat with brass buttons. Typically he rode in a buggy drawn by a spotted brown and white horse that looked like it was right out of a circus. A young girl in town described him as looking “… just like Jesus Christ.”

Character or not, Alonzo Ackerman was a well respected citizen in Danby. He helped with the very first public works project in town (in 1882) when he submitted a bid of only 20 cents a yard to haul 262 yards of gravel for sections of Main Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. In 1910 he was chosen to be one of the original trustees of the newly built Forest Glen School. And for many years, he and his wife, Mary, ran the “County Farm,” a facility that housed and looked after the old and indigent in this area.

Lon Ackerman’s home was on St. Charles Road just east of Stacy’s Corners and not far from where his parents first settled. The house originally faced north toward St. Charles Road. Much later it was turned around to face south on Muirwood Drive, where it sits today. Ackerman died in 1917 and is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery along with his wife of 61 years.

Marcellus Ephraim Jones

Marcellus Ephraim Jones was born in Rutland County, Vermont and moved to Danby in 1858. He enlisted to serve in the Civil War from 1861-1865 and was part of the 8th Regiment of Illinois Volunteer Cavalry, which was mustered into service at Camp Kane on the eastern bank of the Fox River in St. Charles, IL.

Jones is best remembered for firing the first shot at the Battle of Gettysburg during the Civil War on July 1, 1863. He was in command of the cavalry picket post on Chambersburg Pike when he borrowed a Sharps carbine from Sergeant Levi Shafer of Naperville to fire a warning shot above an approaching mounted Confederate officer. Outnumbered, the Cavalry held their position for almost three hours as they slowly retreated towards town in a delaying action until reinforcements of infantry and artillery arrived. This was one of several battles ensuring the success of the Union Army.

After the war, Marcellus Jones returned to the area, and lived in Wheaton for much of the rest of his life. He died in 1900 and is buried in Wheaton Cemetery.

Copyright © 2025 Glen Ellyn Historical Society - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.